First published by T Magazine on 1 March 2016

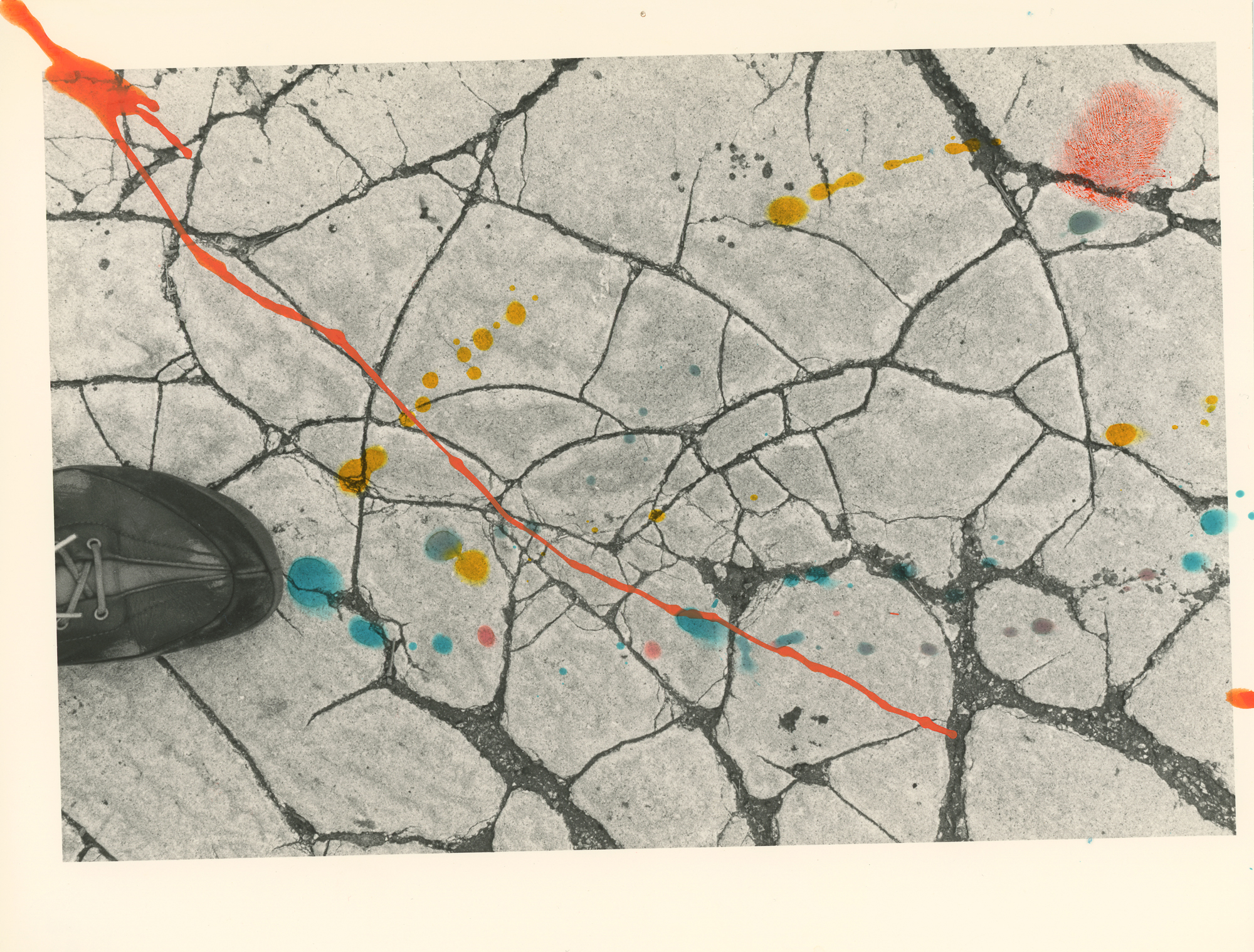

Untitled, Hibi (9) © Masahisa Fukase Archives, courtesy of Michael Hoppen Gallery

To say that the photographer Masahisa Fukase has new work at the Armory Show this week wouldn’t be entirely accurate: His series on display, “Hibi,” was created in the early 1990s. But soon after, the artist fell down the stairs of a bar in Tokyo, entering a coma that lasted until his death in 2012. As a result, his international reputation, which had flourished in the years before his accident, suddenly stalled; while he lay in a coma, his archive was held by a gallery in Japan, and it became near-impossible for European and American galleries and publishers to borrow original prints. “Hibi” was only exhibited by the artist for one evening in 1991 (and is still marked with pinholes from that show), and has never before been seen outside Tokyo. Twelve prints, which will be on view this week, debut exclusively here.

The West was first introduced to Fukase in the mid-1980s, when the English curator Mark Holborn included him in a touring group show, “Black Sun,” alongside three other Japanese postwar photographers: Eikoh Hosoe, Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama. “As a group they created their own language, and it was unlike anything that had been seen in America or in Europe, and that was so refreshing,” Holborn recalls. “There was a sense that Fukase was accessible, and I think everybody, whatever their cultural background — they can see Fukase. They understand it.”

There’s a soul-searching quality that runs through much of the artist’s work. His most celebrated project, “The Solitude of Ravens,” was made in 1986 following his breakup with his second wife, Yoko Miyoshi. The images, depicting the ominous birds in grainy monochrome, suggest grief and loneliness: “A very black and very strange, otherworldly vision of nature,” says Simon Baker, the Tate Modern’s curator of photography. “Bukubuku” (1991), produced soon after Fukase discovered that Miyoshi was remarrying, is a series of claustrophobic images of the artist in his bath; he is sometimes playful, but always alone. “There’s a sense in which it was supposed to be funny — definitely there’s humor there — but also there’s great isolation and great pathos,” Baker says.

The series showing at the Armory examines road surfaces in disrepair — “Hibi” translates as “crack.” Unlike Fukase’s better-known photographs, these prints are hand-painted in a vibrant palette of greens, pinks, yellows and blues. The paint application is wildly varied: It is flicked across some images and washed over others. In some instances, the artist has used color to pick out fissures in the road, or water glistening at the edge of a puddle. His own fingerprint appears on several prints, red and incongruous, like a signature.

In the years since Fukase’s death, Miyoshi has gained control of his estate; the Michael Hoppen Gallery in London has become her representative, and the work has begun to filter out of Japan and into the international art world again. Currently, two of the photographer’s works, “Bukubuku” and “From Window,” are on view as part of “Performing for the Camera” at London’s Tate Modern. Those who know Fukase’s work will find his trademark melancholy in “Hibi,” where his own ghostly presence is strongly felt — but rarely seen. “It’s very hard for us to determine what ‘Hibi’ is about,” says Michael Hoppen. “We’ve spoken to lots of people who knew him, who didn’t know about this set of pictures. He never talked about it.”